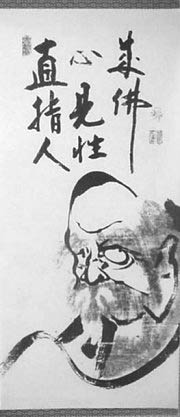

Bodhidharma painted by Hakuin. Public Domain

There is a genre of Japanese Buddhist hymns called Wasan.

Most of the Buddhist Sutras, coming from India, are originally in Sanskrit or Pali language. I am saying “most” because not all of the “original text” of the translated sutras are found in Indian language/script. Yet mostly they are.

And those texts were carried from India to China through West Asian countries, in many cases with hard effort of many years by a few monks, and were put into huge translation projects.

It was mostly these translated scriptures that were introduced to Japan. The sutras are often mixed with Chinese words and Sanskrit sounds transliterated into Chinese.

And then, as the official projects of Sino-Japan trade was seized, and when the generation of monks who could read and speak in Chinese became no more, these were read out in Japanese accent and intonation.

So basically, the Buddhist hymns in Japan were all in mysterious foreign language; which probably worked fine as sacred spells and they are still passed down powerfully to this day. However, it was certainly not easily conceivable for the masses, most of whom could not understand the hymn as an understandable language, even when they appreciated as something special and sacred.

Attempts were made naturally, to make counterparts in the local language, and that is what Wasan is. Its poems and singing are said to have influenced the later folk songs.

Here I am introducing a known Wasan by Zen master Haku-in in eighteenth-century Japan.

白隠禅師坐禅和讃

People’s true nature is Buddha.

Like water and ice,

There is no ice without water

And there is no Buddha without people.

Not knowing it is so close,

People look afar in vain.

It is like being in the water

And crying I am thirsty.

Like being born to a house of rich

And getting lost in poverty.

The karma of six reincarnation

Is the darkness that we choose

From our own ignorance.

Stepping into darkness again and again,

When will you leave the cycle of life and death?

The meditative state of the Mahayana

Is beyond any words of praise.

The Paramitas of offerings and disciplines,

Chanting, repentance, all the practices

And all the good acts recur to it.

Even one sitting in meditation

Will wipe out all the sins.

Then where is evil?

The pure land is not faraway.

Upon hearing this teachings,

Those who follow with joy

Will receive endless happiness.

And not to mention those

Who turn to it themselves

And realise the true nature.

The true nature turns out to be no nature

And then you are already out of the play.

The source and the fruit are one;

That gate is open

And there is only a straight single path.

Take the formless as your form

And wherever you go is your home.

The mindless is your mind,

And whatever you sing or dance

Is the voice of Dharma.

The sky of Samadhi-unity is broad and wide.

The full moon of four wisdom shines brightly.

Then what more will you ask for?

The Samadhi is right here, in front of you.

Here is the pure land of lotus,

And this being is the Buddha.Translation by Paromita.

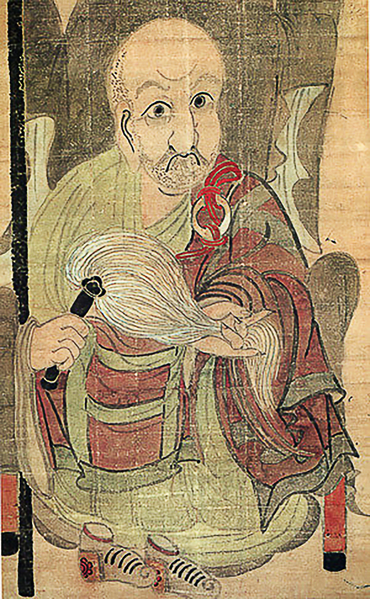

Haiku-in self portrait (1767). Public domain

Haku-in was born in 1685, and was strong in memory from childhood that he used to memorise long songs and teachings to the surprise of the adults.

On the other hand, he was naughty and could be violent as a child that he sometimes bullied small creatures to death. But one day, when he was eleven years old, hearing some teachings by a monk, he looked back on his own doings and feared greatly that he might fall into hell. From then on he started praying to the deities with sincerity.

Studying the sutras and practicing meditation, young Haku-in wished to become a monk, but his parents did not allow. When they finally did, he was fifteen years old.

However, in the very next year of when he entered the monastic world, he became disappointed with Buddhist teachings that he started to pursue literature as the means to save human soul. It was after he became twenty years old that he returned to Buddhism as a monk.

Practising ardently, Haku-in had an experience of enlightenment at the age of 24, which only led him to arrogance, until he met his next master Shoju, who taught him with utter strictness of both physical and verbal abuse. One day, he went to beg for alms in a state without any concentration of mind, that an old lady, whose words of refusal did not reach absent-minded Haku-in’s ear, hit him to the ground. When he regained his consciousness, his state of awareness had totally shifted, and his master recognised it immediately when he went back.

… Like this, his story is quite interesting, but I might take up the rest another time. Haiku-in eventually became an important figure in popularising and establishing the place of Zen in Japan. He is known for the self-healing method that he learned from a senior monk to heal himself when he fell into a kind of neurotic disorder due to years of hard practice (You can search for “Yasen Kanna” if you are interested in this, there are a couple of translations available online). Many writings, calligraphies , and paintings that he made to communicate Zen to people are left.

I am personally a big fan of his paintings.

I wrote his story based on Kimihiko Naoki (1975)’s “Hakuin Zenji; health method and stories” (Nihon Kyobun Sha).

No Comments